I’ve always thought there was something morbidly beautiful about thick clouds of factory smoke backlit by late afternoon sun. Thus were my thoughts several days ago as my friend Nickson and I traveled to his home on the unfenced southern border of Nairobi National Park, passing belching factories and numerous power line pylons hugging the east side of the park.

Google Nairobi National Park, and you’re barraged with a series of articles containing the words “only” and “first”. Located directly south of Nairobi, NNP was the first national park in Kenya, gazetted in 1946, acting as the spark for tourism to become Kenya’s greatest industry. It is one of the only places to spot the endangered eastern black rhino, of which about 700 remain. It is also the only national park located in an urban area, and people take a certain pride in saying its the only park where you will be able to take photos of wildlife with skyscrapers in the background. What you don’t hear about are the industrial compounds that may also appear in your photos, and which encroach slowly but ever so reliably onto park land. You also don’t hear that the park is already contained by electric fencing on three sides, open only to a rapidly developing dispersal area over the Mbagathi River to the south.

Since the park only comprises 117 square kilometers, and is so heavily pressed by development, the southern Kitengela dispersal area (where I’m currently residing) is critical for wildlife such as large herbivores and lions to move between NNP and the Athi-Kapiti plains. Although the dispersal area is facing subdivision and other development pressures, there are multiple efforts underway by Friends of Nairobi National Park, WWF, The Wildlife Foundation, and others to incentivize current landowners to keep their lands open and unfenced, giving the wildlife passage.

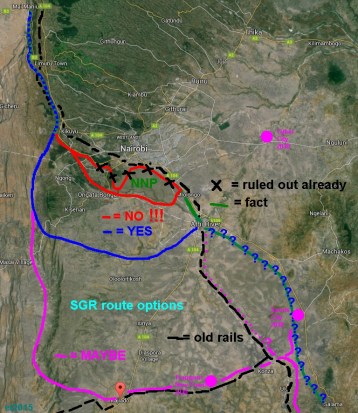

The newest battle for the preservation of NNP has begun over what may be the most devastating development pressure the park has ever faced: a railway running through the park and/or the dispersal area. Developers of the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) have so far listened to the multitude of angry community members and conservationists, and currently have agreed to divert the railway to the southern border of the park, proposing to build an overpass along the Mbagathi River. Portions of the park have already been de-gazetted for development purposes, and running a railway through the park could have been a fatal blow. However, although it seems as if local conservationists have gained some ground, pushing the railway construction south to the border of NNP would still dramatically impact the thousands of animals moving in and out of the park. This isn’t just about impacting seasonal migrations; every day here at Nickson’s I’ve walked outside to see zebras, wildebeest, impala, and giraffes freely roaming in and out of the park to graze these lands. The most ideal option being proposed by conservationists is a reroute far to the south, which would avoid the dispersal lands, yet Kenyan officials have denounced this as too expensive (which is seeming to not be true). To further make the case for the southmost route, it seems that route is supported by residents in that area, while residents around here are still waiting to be involved in conversations about potential loss of their land- only having received infuriating silence from officials thus far.

Because of these development pressures, many have expressed concern that Nairobi National Park will soon become completely isolated, “like a zoo”. Yet some may argue that this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and may be inevitable. Although it is of course ideal to maintain landscape connectivity and ecological authenticity if at all possible between parks and reserves, there are many parks and reserves in parts of sub-Saharan Africa that are completely fenced. Many of these parks are managed accordingly, with periodic hunting or culling to maintain populations, and plans in place to prevent genetic inbreeding of wildlife. Of course, many of them are heinously mismanaged as well. Yet research on fenced wildlife reserves and sustainable management of these reserves is only increasing as time goes on, in correlation with increasing development and subsequent habitat and connectivity loss.

I, personally, am interested in creative community approaches to sustaining landscape connectivity and wildlife habitat. I am for the wildlife, through and through, yet I’ve grown to realize that necessitates being for the people as well. As much as I’d like every human to learn to put the needs of wildlife on the same level as their own needs, and fall into rapture at the sound of a hyena yipping on the savanna at dusk or the view of a giraffe silhouetted against the sunset, those aren’t realistic desires. So in this world of more and more humans and less and less of everything else, I’m keeping my mind open about our options.

Great post! Very informative.

LikeLike

Thanks for the post! I didn’t know about the history of the park, its urban context, or the issue of the railroad (basically all of it except the appreciation for wildlife parts…).

LikeLike